Note: this article was first published in 2020.

Offshore wind must effectively engage coastal communities. It can save money and avoid heartache through the lessons of other clean economy sectors.

"Solar and onshore/offshore wind developers. Download, read and take action.… You'll thank Mike Casey and me." – Susan Munroe, Director of Economic Development, Chambers for Innovation and Clean energy.

Offshore wind (OSW) is a disruptive new sector within the power industry. Like other clean economy sectors, its success will rely partly on effectively engaging local communities. In OSW’s case, it’s the communities where project infrastructure will make landfall that will have control over whether or not OSW farms are built.

The increased professionalization of professional NIMBY pushback (Not in My Back Yard) threatens that success. However, OSW can save time and avoid heartache by adapting the hard-won community engagement lessons from other clean economy sectors.

We’ve analyzed the community relations experiences of solar, onshore wind and the PACE sectors for portable lessons to other clean economy sectors, including OSW. We’ve identified a three-stage, “Clean Economy Mistake Path” that is expensive to enter and can end at project fatality.

This initiative stems from my presentation at last fall’s Offshore Wind Conference in Boston, hosted by the American Wind Energy Association. Shout out to Nate Mayo of Vineyard Wind and several other audience members who encouraged us to expand last fall’s presentation into a more in-depth format.

You can read more below, or download this as a PDF here.

Introduction

Last fall, I spoke at AWEA’s Offshore WINDPOWER Conference. Preparing for that appearance prompted my firm to look at the experience of other disruptive, clean economy sectors that are locally regulated. For offshore wind (OSW), which is regulated at the federal, state and local levels, a valuable pattern emerged from the collective experience of rooftop solar, onshore wind, home sharing and PACE lending. While the new pandemic and recession make all that seem ages ago, we think the lessons provided by those other sectors are still worth presenting to the OSW sector. Each of these other clean economy sectors found costs and heartache by bumping into the realities of being locally regulated.

With hindsight, many in those sectors acknowledge they should have solved for those predictable challenges in their respective business plans — right from the start.

What is the NIMBY Effect?

Too many companies in those sectors had to compensate for their early underinvestment in public affairs by having to build programs while dealing with expensive problems with NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) opponents.

NIMBY campaigns are professionalizing. They are getting more sophisticated and effective, they are being supported by professional organizers, they have secured funding by incumbent sectors, and they connect through online resources. As Bloomberg News has reported, the costs of underinvestment in public affairs are adding up for companies in clean economy sectors, a trend that’s expected to escalate.

The onshore wind industry is now seeing half-billion-dollar power plants killed because 50 people shout at officials in a county commission meeting. Airbnb had to struggle to fend off attacks from the hotel lobby on their ability to operate in New York City and other major cities. Despite its huge popularity and tiny viewshed, even solar energy is getting hurt by professional NIMBYism. Many laughed when Woodland, North Carolina rejected a solar farm in December 2015, because some residents worried the solar plant “would suck up all the energy from the sun and businesses would not come to Woodland.”

The costs of underinvestment in public affairs are adding up for companies in clean economy sectors, a trend that’s expected to escalate.

No one’s laughing now.

Last fall, sPower almost lost its permit to build a utility-scale solar farm in Spotsylvania County, Virginia—70 miles south of where I write this. Earlier this year, Bay W.A. Renewables lost its permit for a solar farm on 1,600 acres in nearby Culpepper, Virginia. After beating Bay W.A., leading opponent Susan Ralston said she…

“...plans to turn her [local] 501(c)(4), Citizens for Responsible Solar, formed this spring, into a vehicle to help other citizens groups fight solar projects all over the country. ‘You see this story played over and over again,’ [Ralston] said. ‘The states have just been overrun with solar. The land is cheap, and these developers come in. They come in and the citizens don’t know this is happening, and when they find out, it’s too late’.

Even those sectors, such as scooter companies, that aren’t disrupting powerful incumbents have run into problems. As of this writing, time and street limits on scooters in Atlanta have led to the state of Georgia to consider a complete ban on all shared electric scooter companies statewide. Lyft has seen the writing on the walls and pulled its scooters out of Atlanta. The results are increased costs for many, project death for some and a few companies now completely out of business. The big message from the combined experience of these other sectors is that securing community acceptance is a business-critical task.

Social Acceptance of Offshore Wind Power Projects in the US

OSW can take a different path. Even with only five operating turbines to date in the US, the sector is not a collection of startups. Far earlier than in other sectors, OSW is being driven by experienced, deep-pocketed players, drawn to the tremendous growth potential in the $70B addressable U.S. OSW market. The current range of large companies pursuing OSW have no excuse for bootstrapping community acceptance by skimping on budgets, staff and scale.

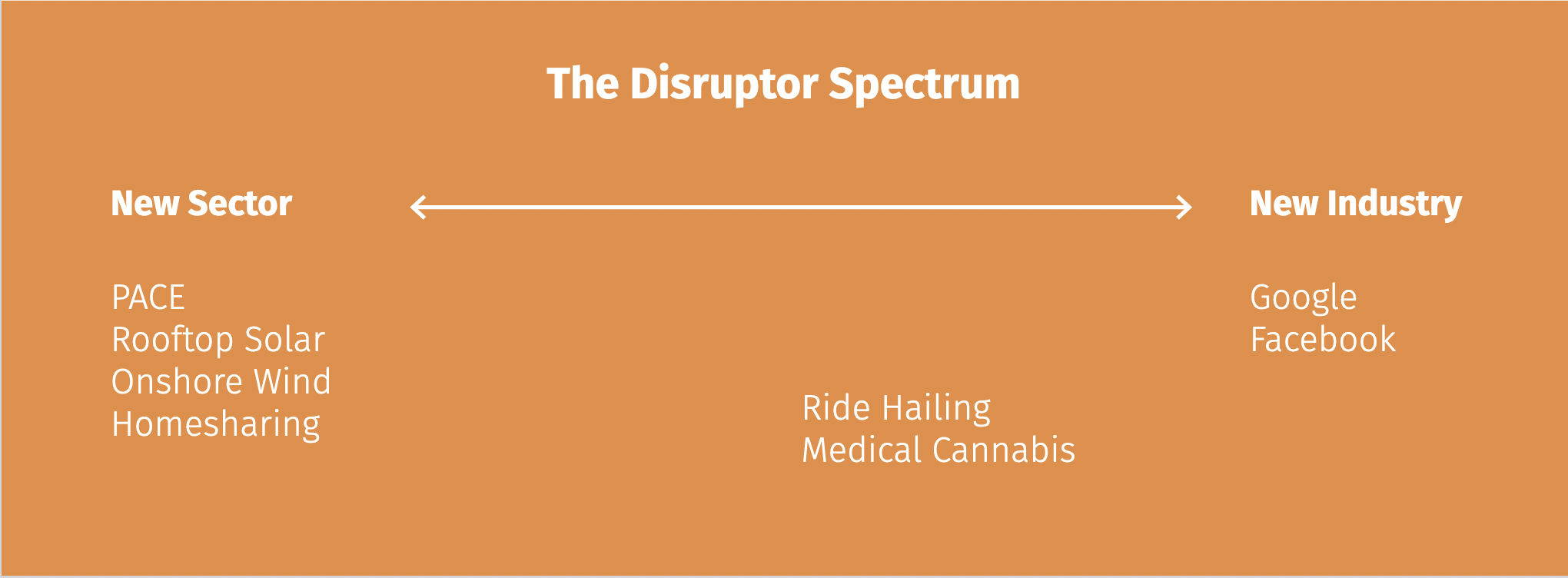

Why are so many clean economy companies late in scaling their public affairs? One reason is that many companies see themselves as part of a new industry, when they are actually a new sector within an industry dominated by incumbents with the ability to respond to new, disruptive players.

At the dawn of the internet age, Google and Facebook were creating a new industry. Yes, both companies proved tremendously disruptive over time, but they had a lot of run room before the disrupted could see the threat and respond. Ride hailing and medical cannabis are just a bit off the “New Industry'' side of the scale. Ride hailing is pushing back against a taxicab industry that’s usually quite weak, unless you’re in London. Medical cannabis will displace some types of pharmaceuticals, but most people in that sector tell me they expect the drug and tobacco companies to buy up leading cannabis players. In other words, they will join — not fight — the dope industry. But like solar, PACE, onshore wind, and home sharing, OSW is not a new industry. It’s a new sector out to take market share from incumbents who aren’t going to act like doormats for the new guys.

OSW has already had an early taste test of community pushback and its costs. The first attempted project, Cape Wind, was killed by attacks from wealthy neighbors who included one of the Koch brothers, the Kennedys and retired CBS anchor Walter Cronkite. The burgeoning OSW sector has now had the federal “pause” button pushed mainly as a result of advocacy from commercial fishermen. Fishermen are admirable people, risking their lives to put seafood on our kitchen and restaurant tables. But they also are part of an industry that sees OSW as a disruptive threat. The different sectors of the fishing industry — scallops, squid, etc. — have banded together to use local voices to affect OSW’s fortunes at the federal level. The OSW sector is still working out how to counter the fishing industry’s tactics by promoting the local job creation and climate mitigation benefits OSW provides.

The bottom line? There’s a big difference in how public communications should be scaled from the start if you’re a new sector vs. a new industry.

Offshore Wind Communications Challenges and Mistakes

Advocacy Valley of Death

OSW would benefit by understanding that it’s entering into the Advocacy Valley of Death: Big enough to be a disruptive threat, but not ready to respond to the reaction of the disrupted. Look no further than the seemingly obscure, 2010-16 Coast Guard “study” prompted by pressure from Maersk, the leading global shipper with significant interests in the oil and gas industry. The Atlantic Coast Port Access Route Study was riddled with lobbyist influence, and it resulted in a call for OSW turbine setbacks from shipping lanes that are 5x those required in Europe. While more recent studies have countered its recommendation, ACPARS was essentially a trial run for lobbyists looking to stop OSW’s growth.

OSW would benefit by understanding that it’s entering into the Advocacy Valley of Death: Big enough to be a disruptive threat, but not ready to respond to the reaction of the disrupted.

Clean Economy Mistake Path

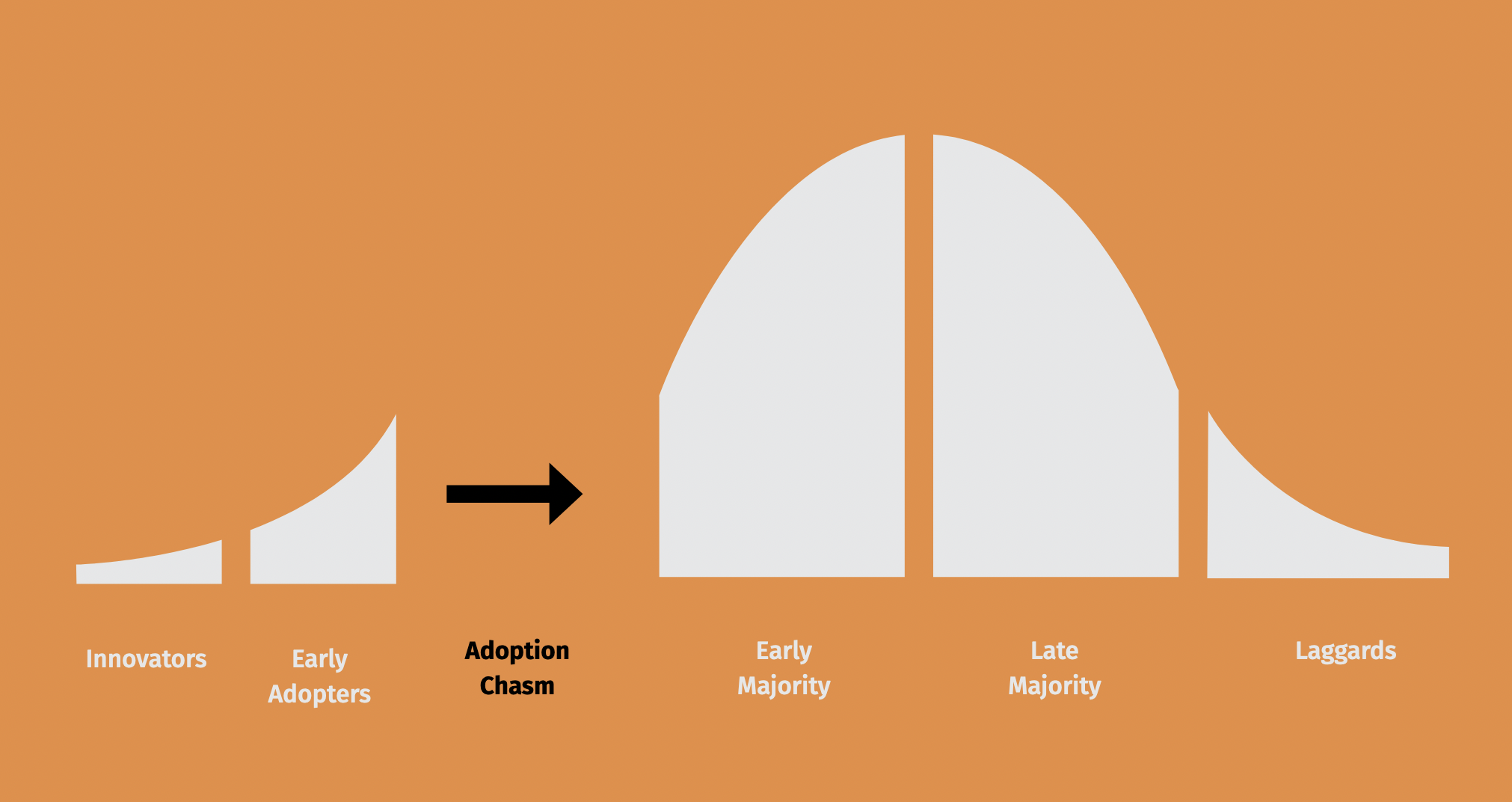

Overlay the experiences of the four other clean economy sectors, and the resulting pattern forms what we call the “Clean Economy Mistake Path,” which takes place in three phases. First is the Green Zone, or “go” stage. New companies rush to establish a commercial presence and claim market share, working under the demands of cash burn from limited funds. Because they’re doing something new, mistakes are inevitable. In the Yellow Zone, disrupted incumbent sectors convert early mistakes into a problem for people in communities considering whether or not to host the new sectors’ projects.

Onshore wind is in this zone now, featuring the professionalization of NIMBY organizers, strong online connections between the NIMBY groups and quiet funding by incumbent sectors. As far back as 2012, the anti-wind energy marketing of fossil fuel operative John Droz and the American Tradition Institute were exposed. Anadarko Petroleum was caught trying to manufacture the perception that there was a wind turbine fire “crisis” throughout the American West. In the Yellow Zone, the goal of incumbents is to convert a one-community problem into a highly publicized, multi-community issue. We’ve recently finished a series of interviews with the onshore wind developers. Almost to a person, its leading communicators acknowledge how easily complaints about wind farms go viral across state lines.

Stay out of the Red Zone. It’s expensive, high stakes and agonizing — even when you survive it.

This also happened to the residential PACE industry (R-PACE), and it effectively cost R-PACE the entire anchor market of California. It’s then just a few steps into the Red Zone. There, a new sector’s issues are flagged to analysts tracking valuations of that sector’s companies. The result is a string of pronouncements that the sector’s companies are “troubled,” and “facing significant challenges.” A lead steer on the board begins to panic, and fear spreads throughout the board, resulting in demands that the leadership team fix the problem. The result is an expensive, all-hands diversion from the business plan to desperately bailing out public affairs water from the company boat.

At best, the company pays firms like mine crisis communication-level fees to right the ship. At worst, the company dies, like SolarCity effectively did after the Christmas Eve bait-and-switch in Nevada — engineered on behalf of NV Energy by an ethically challenged public utility commissioner. Trust me, you want to stay out of the Red Zone. It’s expensive, high stakes and agonizing — even when you survive it.

4 Steps Towards the Mistake Path

We’ve identified four factors that drive companies in disruptive sectors to get on the Mistake Path.

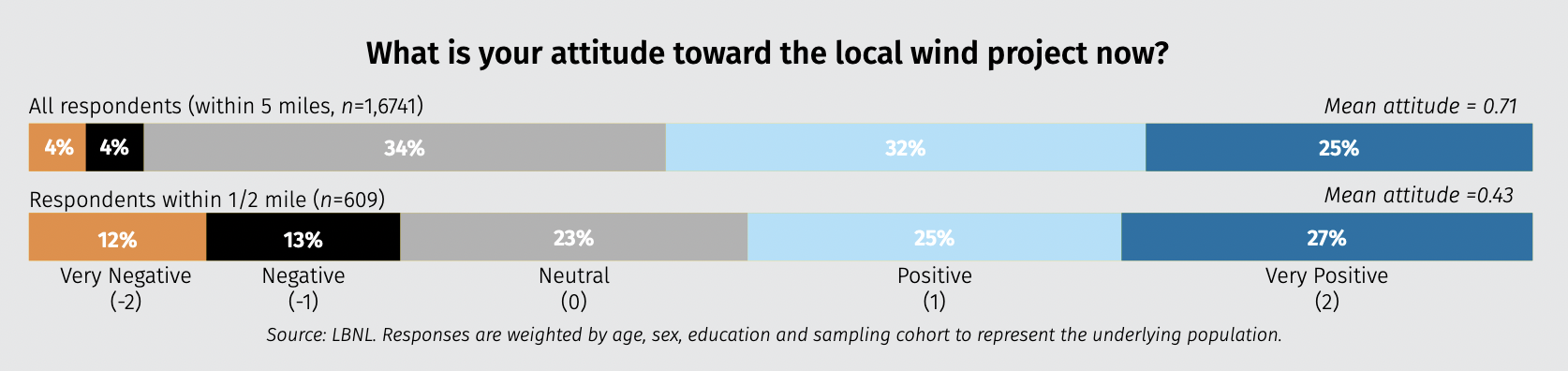

1. Excessive belief in the meritocracy of policy debate, regulatory institutions and the motivations of elected officials

Hedge fund-controlled Gatehouse Media has bought up dozens of struggling local newspapers across the country, converting them into the Dollar Store of journalism. The company produces the equivalent of cheap trinkets by cutting news journalism corners at every turn. Its 2017 hatchet job, written by a summer intern, painted a sensational picture of a wind turbine health “crisis” among rural neighbors of wind farms. A month after the Gatehouse hit job ran, Berkeley National Lab came out with the definitive study of attitudes among those living within five to a half mile of wind farms. The study found that over 50% of people who live within a half mile of a wind farm had a positive or very positive experience with the nearby turbines. But the Gatehouse series was a shot heard much farther than the fact-based study by Berkeley National Labs.

We’ve noticed that the younger a clean economy sector is, the more likely its members will see their differences before their shared interests. That makes forming effective coalitions and associations more difficult, as various consultants and executives compete to form the industry coalition they can control to their benefit. The result is turf battles that fetter common-good advocacy. This was sadly true when we worked for the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA) during its greatest existential threat, the 2009-10 phony Solyndra “scandal.” This ruse was pushed by the fossil fuel lobby. It featured an FBI raid, dozens of Congressional hearings and an estimated $800M in SuperPAC ads spent attacking President Obama’s “green energy” program. At the time, there were at least four ad hoc splinter groups competing with SEIA for dollars and attention. Their differences were trivial compared to the size of the threats the sector faced, but the divisions still had to be navigated by then-SEIA President Rhone Resch. The result was a significant drag on response times and effectiveness, despite SEIA’s best efforts.

3. Poor Hiring

Often when private sector startups run into government affairs problems, they ramp up hiring. That hiring sometimes takes one of two unhelpful forms: 1.) “Friend and family hiring” of people who lack experience but are familiar and trusted. 2.) Star chasing a “big name” who once held down a high-profile government job. Neither approach accounts for the amount of relevant experience the new hires have had in getting politicians to treat companies fairly.

4. Magical thinking about budgetsI heard once that there’s a Zen Buddhist saying: “You can stand in the circle of what is, or you can stand in the circle of what should be while shouting at the circle of what is.” Said another way, disagreeing with reality doesn’t change it. Politics and policy are a full-contact sport. If your company is out to take market share from active incumbents in an industry with significant regulatory exposure, you will be fought, not ignored. And captured regulators will be part of the toolset used by incumbent sectors. The messiness and slow pace of policy decisions isn’t a reason your company can sit out those decisions. Hiring the right people to execute well-designed, effective programs costs real money that’s guaranteed to be more than you want to spend. But spend you must.

Offshore Wind Best Practices to Improve Public Acceptance

With just one pilot project in the water, OSW has the luxury of choosing between either investing at scale to influence public acceptance of offshore wind power projects in the US, or rolling the dice at the craps table. If OSW wants to avoid the public affairs heartache of other clean economy sectors, there are five practices it should consider.

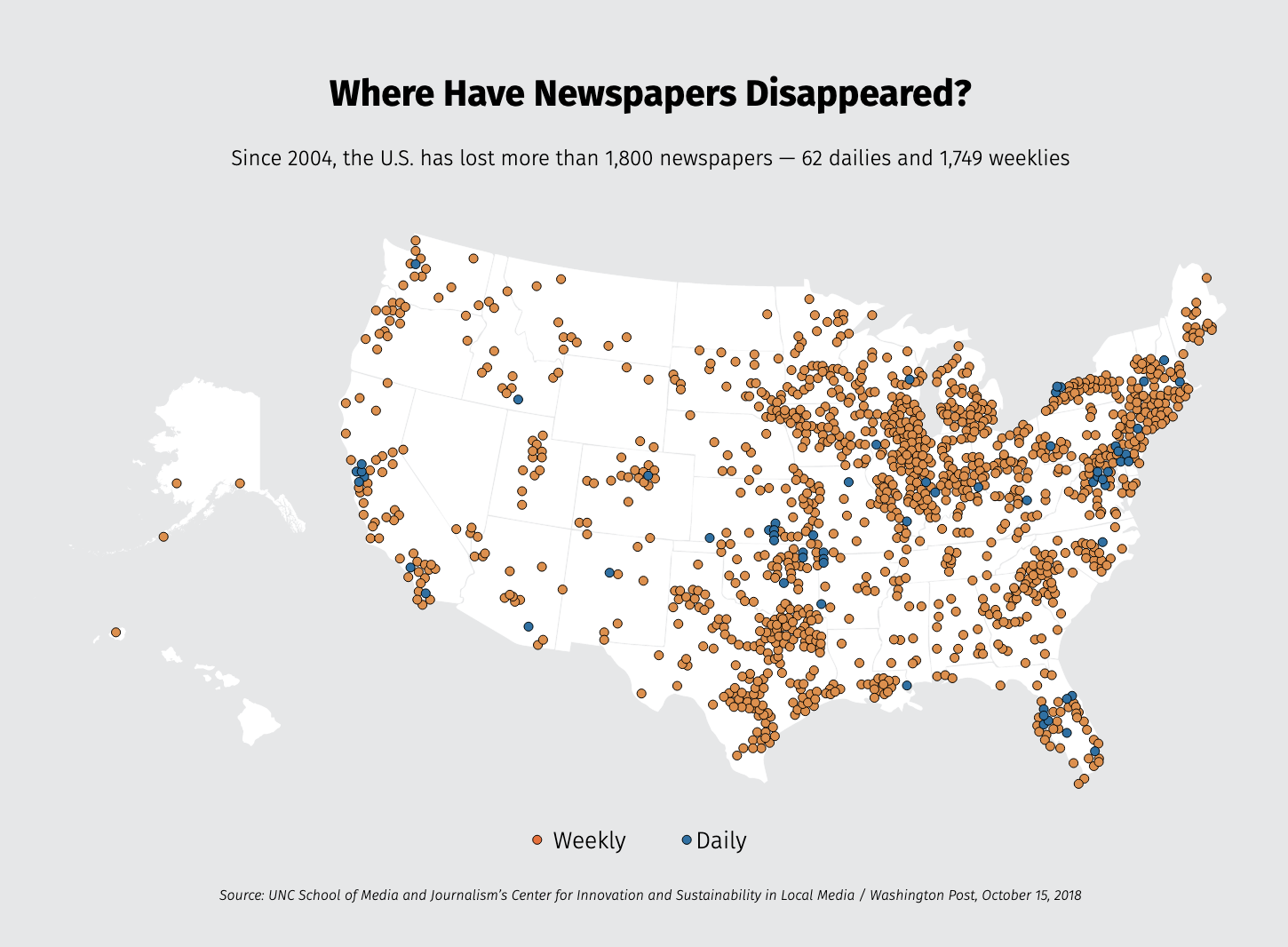

1. Invest in the online conversationLocal communities are increasingly making early-stage decisions online. This is particularly true in small communities, which make up the lion’s share of the 1,300 towns that are now “news deserts” — communities with no local news media serving them.

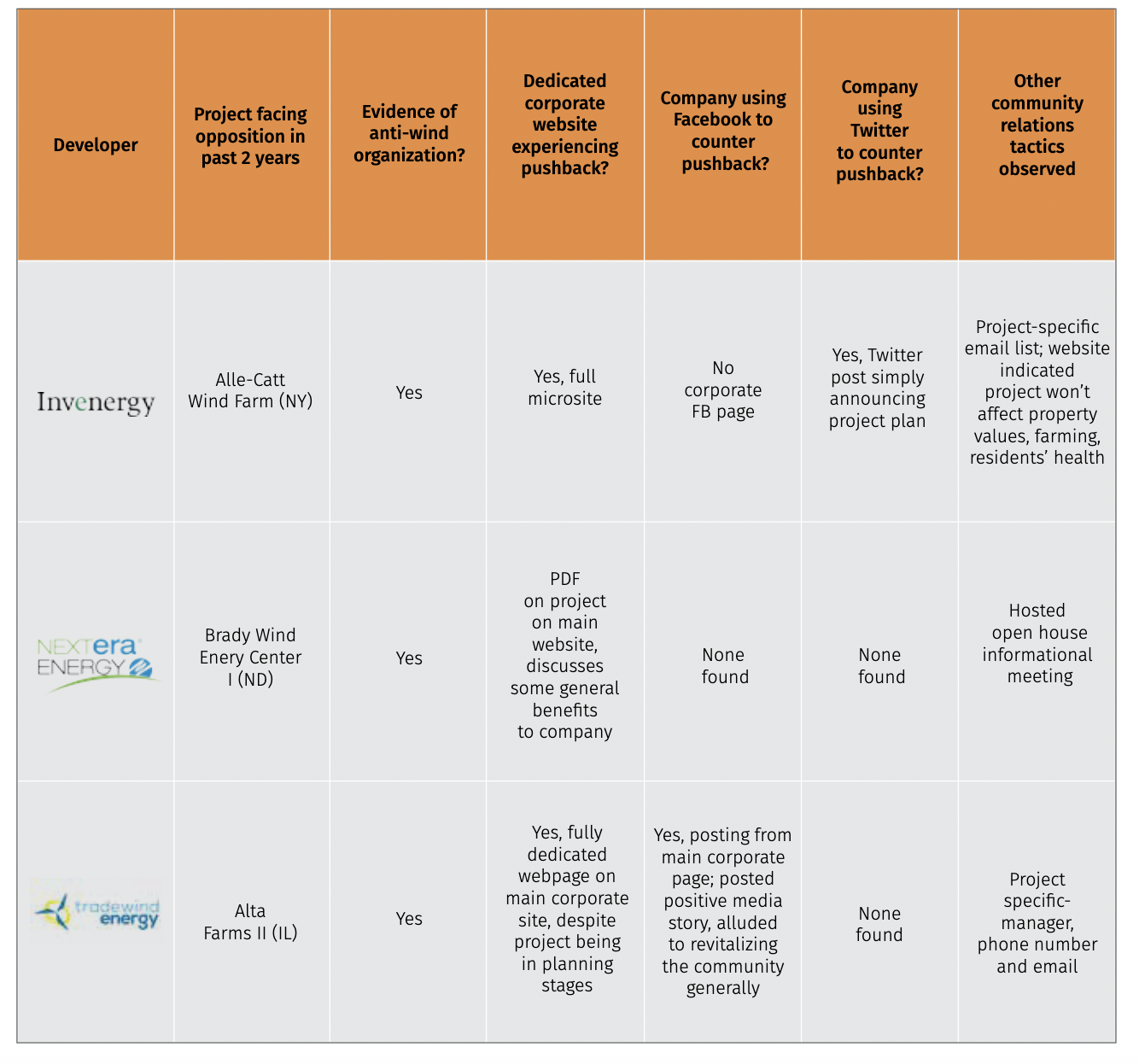

Into that void has stepped Facebook, which has become “the new town square.” (H/T to Paul Copleman of Avangrid). In fact, in its groundbreaking survey of small-town news consumption habits, Apex Clean Energy found that Facebook was a top news source in rural communities, including those considering whether or not to host a wind farm. We conducted the first-ever analysis comparing the online pushback from NIMBYs with the online responses from the top onshore wind developers. Only one out of 10 had anything resembling a proactive digital program. The consensus is that NIMBYs now organize online, then show up in the room. You underinvest in Facebook and other digital platforms at your company’s peril.

2. Win the race to define

Any large-scale clean energy project is the equivalent of an issue or political campaign, and every campaign is a race to define. He or she who frames first creates an advantage that’s difficult to overcome. We still find that among clean energy developers, the legacy mentality of quietly working regulators is the norm. It’s also a de facto guarantee that you will start the race with your shoes tied together. Being quiet is a losing strategy in an age of increasingly professionalized NIMBY opposition.

A marketing strategy should be applied for every wind farm, treating it as a product that must be narrated. Use compelling, plain-language framing that’s anchored to a core need in the community. And, that definition has to be driven home through visual storytelling (read, video), narrated by people whom locals find relatable. Narratives from people trump facts and figures — always. But the good news is that the OSW industry has a robust potential supply chain and employee base to utilize. They are the people who should start the conversation for your company. It’s crucial to form a supporters group for your project immediately, and then constantly build it through potential vendors and potential employees. If your company can show growth online, it for opponents to argue against community momentum for your project — rather than allowing the opposition to grow its moment and force you to catch up.

3. Use digital to engage, not distribute

Too many companies in the clean energy sectors treat digital platforms as new and cheaper forms of distribution. Basically, another version of the traditional news release. The “post and forget it” approach is leaving communications power on the table, and it stands in stark contrast to the online NIMBY conversations. It’s critical to fully integrate the use of digital tools with your in-person community acceptance efforts. If your company has to present at the local library to a community group, why not use your project Facebook page to share favorable participant comments with those who didn’t attend? If you use your digital platforms to parallel the back-and-forth of in-person conversations, locals are much more likely to feel heard. In fact, online critics are usually an asset. Their arguments on your project’s Facebook pages show in real-time changes in opposition arguments. Your response to them — polite, clear and consistent — will be watched by supporters, who will be emboldened by your proactive response. Note that the effective use of digital tools requires dedicated staff capacity to constantly engage local citizens in the online conversation.

4. When hiring, don’t equate expertise with just having opinions

We’ve met a lot of public affairs leads, line staff and vendors for clean economy companies over the last 15 years. The vast majority are very committed to transforming the U.S. economy to a more sustainable footing. But many are the product of the two misguided hiring approaches we listed earlier. You wouldn’t hire someone like me to be your lawyer or your accountant. Don’t hire people with no successful experience driving public affairs outcomes. Whether it’s employees or vendors, hire people who have successfully done for others what you need them to do for your company.

That experience should include:

- Putting people into office or escorting them out of office by working on political campaigns.

- Serving elected officials while they are in office — particularly at the level of government at which your company is focused. A stint in a Presidential or Governor’s Administration as a policy wonk provides no guarantee that a job candidate or consultant knows anything about the rough and tumble of electoral politics.

- Pressuring elected officials or regulators to take the right action through successful public affairs campaigns.

5. Invest real money in controlling your fate

When it comes to offshore wind challenges, this in particular is a big one. I spent a fair amount of time in 2017-18 working with the public affairs heads of the early OSW players. Together, we hammered out a compelling strategy to handle the grave concerns about how Trump’s past business hostility to OSW would play out in his Administration. It was a reasonable concern, and the group crafted a sound plan over several months. However, when it came time to pass the hat for funding its own public affairs success, each company thought and played small-budget ball. That is beginning to change with the addition of more and bigger companies. But the lesson stands — if your company’s fortune rests on public affairs outcomes, don’t engage in magical thinking about what things cost. There is no green philanthropy riding to the rescue of a for-profit industry populated by large global companies. You must fund your own public affairs fate at a level that matches its criticality to your company. When it comes to public affairs, nothing’s free. It’s not even discounted. It’s only effective or not. And given the importance of our emerging sectors, we should insist on doing what works.

When it comes to public affairs, nothing’s free. It’s not even discounted.