We recently teamed up with our friends at Conservatives for a Clean Energy Future and the folks at Embold Research to do something untried: use cutting-edge public opinion measurement tools to go deep on attitudes toward renewable energy in one rural bellwether community. We first presented these findings at the CLEANPOWER trade show in Salt Lake City.

Why do that?

Renewable energy has scaled dramatically, dropping costs across every category… except winning permission from a local community to host a wind or solar farm. In fact, the community engagement leads at every developer and asset owner we’ve talked to say the same thing: community acceptance is getting more expensive, time intensive and difficult to secure.

I’ve made the case (here, here and here) that this isn’t an accident. Instead, it’s the predictable reaction of mature energy players with deep experience in weaponizing government and disinformation to prevent clean energy from taking market share. It’s the disrupted reacting to disruption from disruptors.

We’ve now reached a stage of renewables’ growth in which plans for a $350M renewable energy power plant get scuttled because 50 locals organized on Facebook to show up and scream at the swing county commission vote on a project permit. Loss of a potential project is an obvious financial risk. But every time there’s a fight over a project, the dust that’s kicked up drifts into state capitols and governors’ mansions, increasing the drag coefficient that incumbent sectors really, really want renewables to have.

If we're going to continue accelerating the transition to a clean energy future, we need ways to solve this growing problem. We suspected one path sits in communities that already host operating projects.

Bellwether: Huron County, Michigan

So, we partnered with Conservatives for a Clean Energy Future to look at one such community – Huron County, Michigan:

- Rural – 33K people

- Conservative – voted for Trump 69%, Biden 30%

- Heavy renewables development – the highest density of wind turbines in the state

- Increasingly acrimonious – projects have faced growing opposition, and some townships within the county have passed anti-wind moratoria

- Renewables already delivering benefits – there are a number of specific, local infrastructure improvements that have been paid for by tax revenue from wind energy

Findings

To measure local residents’ views of renewables, we used a new polling method developed by Embold Research, Dynamic Online Sampling (DOS). You can read more about it on Embold’s website, but suffice to say here that DOS is cheaper, faster, more accurate and is able to go deeper in a specific community than legacy polling.

Among other things, we learned:

- The heavy presence of renewables in Huron County is well known among locals

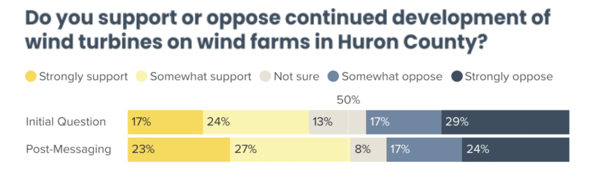

- By 5 points, residents opposed more renewables

- A plurality of respondents didn’t want more renewables in their county

- Locals want operating renewable energy farms to fund specific infrastructure improvements – exactly what the industry is doing

Yet, when told about several specific infrastructure improvements that the industry funds, the respondents moved from -5 to +9 in favor of more renewables in the county. A 14-point swing typically takes a battery of questions in traditional polling. Here it happened with one question. With a minimum amount of basic information, public opinion on renewable energy moved significantly.

The only conclusion we can draw is that the industry is under-communicating its benefits – the tangibles, such as new stadiums and parking lots – to the communities that host renewable energy power plants.

How does that apply to asset owners? To decide, review this checklist:

- Is your company communicating with any frequency to the communities that host your wind or solar farms?

- Are you doing that effectively with two-way dialogue, or just occasionally distributing information or giving to local charities?

- Are those communications based on an intentionally designed program?

- Is your program designed to produce benefits that compound the other ways your company publicly communicates?

Only you can know how your company does against that checklist. Companies’ programs will be on a spectrum, and I know of at least two developer-owners who meet the four criteria above. But I suspect many others land somewhere between ghosting host communities entirely and throwing turkeys off the back of the truck at Thanksgiving.

By contrast, the oil and gas industry has invested hundreds of millions of dollars over decades, growing deep roots and making itself iconic in host communities. They’ve used everything from massive propaganda campaigns from the likes of the American Petroleum Institute, to localized efforts such as the Louisiana Shrimp and Petroleum Festival (who knew?).

Renewables don’t have those budgets, for sure. But none of our companies have a reason not to do the basic stuff that’s right in front of us.

There’s a growing cost to under-communicating

The under-development of host community public support comes with a growing, two-fold opportunity cost.

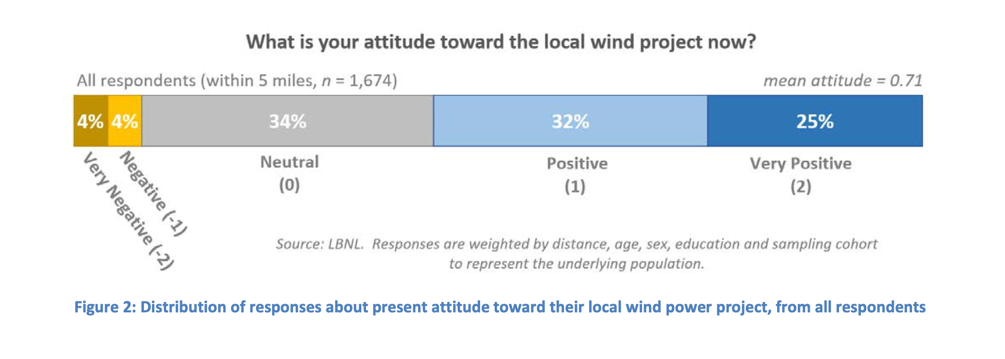

First, if we want to make the case to communities why they should host a project, what better proof point is there than a similar community with residents who are happy to have decided “yes”? Note that most wind farm neighbors are happy to live next to one, according to the definitive survey taken in 2018.

So, what if we had enthusiastic neighbors of operating projects who’d communicate – even remotely – with people considering having a wind or solar farm as a new neighbor?

Second, if we grew and curated our neighbors’ support for what we do for them, and we documented the growth of that support to politicians, guess what? We become way harder to ignore or cross when it comes to the next 10 years of public policy asks (more on that in an upcoming piece). Right now, the best thing renewable energy companies can do in the halls of government is to be charming beggars. Disagree? Then DM me on LinkedIn with one politician at any level of government, anywhere in the country, who actually fears the political consequences of going against the renewable energy industry. I’d love to be wrong on this.

The “1% approach”

What if asset owners took one percent of total construction costs and devoted it to an annual program of developing, curating and leveraging public support once a wind or solar farm is operating? That would be more than enough to support a basic program featuring:

- Visitor centers

- Trained, well-scripted local tour guides

- Part-time community relations coordinator charged with attracting tour groups, not just accepting requests for a visit

- Use of a CRM (customer relationship management) platform to track visitors and engage them post-tour through regular communications

- Strategic use of Facebook – the new rural newspaper – to feature power plant employees to their neighbors

- Use of new polling methods and “A/B” testing of digital ads to track the resulting growth in public support in the local community

- Showing that growing support to public officials with both numbers and tours – start with county commissioners, then work your way up to the governor

- Engaging supportive local officials to help announce the real infrastructure improvements, such as police stations, or libraries, that renewable energy has paid for – they spent political capital to help you, are you spending financial capital to help them?

Those are basic elements of a basic program. There’s nothing sacrosanct about them, and there’s plenty of room to make them better. But the point is that every wind or solar farm should have a program with at least these components. Yet very few of them do.

The result is a communications vacuum that’s filled by the “told you so” crowd and operatives from incumbents uninterested in giving up their market share. Being negatively defined in our current host communities raises community acceptance costs for future projects, and it costs us in statehouses, capitol buildings, and in Washington.

We save pennies so we can spend millions of dollars later. I’m in PR because I suck at math, but even I know that this doesn’t add up. The good news is that there’s a better way, and it’s waiting for the first mover to seize its fate and show the rest of the industry the way we make the most of what we’ve already done.