Before publishing this paper, I had to change its subhead from “Angry about Joe Manchin? Take a number,” to what you read above.

Many working for the clean economy transition are now relieved by the senator from West Virginia because his change of mind has enabled the hugely significant climate bill to become a reality.

It would be a tragic mistake for us to put our feet up, figuring all’s well that ended well. Let’s be clear: This climate reconciliation bill almost didn’t happen. It’s smaller than it could have been.

Worn down by Joe Manchin? Take a number. Want to do something about him and his kind? Look in the mirror

Joe Manchin's version of the bill offers significant giveaways to fossil fuel interests. Happy as we are with winning, it would be crazy to feel satisfied with how we got here. We were underbuilt for the moment, and it kept us as political beggars.

We got lucky.

For a moment, let the reality of what we were facing sink in: Putin’s reminding us of the cost of relying on petro-states while the accelerating climate destruction crisis is already bringing deadly heat waves, disruptions to food production, elongated wildfire seasons, and even the first waves of climate refugees. Yet our ability as a nation to address humanity’s greatest existential threat was almost immolated by the Supreme Court’s West Virginia v. EPA decision and one corrupt, empowered senator with a coal business side hustle.

As Leah Stokes of U-C Santa Barbara said (before Manchin’s change of heart):

“Over the last year and a half, I’ve dissected every remark I could find in the press from Senator Joe Manchin on climate change. With the fate of our planet hanging in the balance, his every utterance was of global significance. But his statements have been like a weather vane, blowing in every direction. It’s now clear that Mr. Manchin has wasted what little time this Congress had left to make real progress on the climate crisis.”

How did we get here?

The source of the answers lies several decades upstream of this moment.

We’re disrupting several sectors with decades of practice in weaponizing government to protect market share. Pretending that’s not so doesn’t change reality. I’m working my way through “Master of the Senate,” Robert Caro’s exhaustive, third tome on the life of President Lyndon Baines Johnson. It contains a roughly 50-page section detailing how several Texas oil and gas barons get then-Senator Lyndon Johnson to block a second term for New Deal reformer Leland Olds at the Federal Power Commission, the predecessor of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

The oil and gas industry bankrolled Johnson’s political ambitions. It provided him vacations, business opportunities, and even free flights on their corporate plane. The industry didn’t want Olds enforcing the Natural Gas Act of 1938, thereby fettering their ability to price-gouge natural gas customers in large Midwestern and Northeastern cities. Millions of industry dollars were at stake.

To keep their favor, Johnson formed a special committee to review Olds’ nomination, then lulled Olds into complacency about his prospects. All the while, the industry lobbyists secretly compiled a dossier on Olds’ past writings and work as a labor organizer.

Summarizing a long, ugly story, Olds was the victim of a strategically choreographed ambush. Committee members red-baited him with aggressive questions, supported by planted news stories painting Olds as a communist.

Truman was forced to replace Olds with an industry-compliant successor, who undid years of Olds’ pro-consumer reforms. The oil and gas barons enjoyed a windfall of tens of millions of dollars. I’ll bet they spent less than 1 percent of that amount engineering the ambush itself.

Consider that this all took place 70 years ago!

Seven decades is a long time for this polluting incumbent to advance its ability to weaponize government to protect profits. As Steven Mufson of The Washington Post reports, “Republicans threaten Wall Street over climate positions.” Read Robert Kaiser’s “So Damn Much Money,” documenting the rise of modern lobbying, or the “The Polluters,” the definitive history of chemical industry lobbying (Ross & Amter, 2012). The pattern they present is clear and consistent: As polluting industries mature past 50 years, they embed lobbying and disinformation to manage marketplace threats.

That’s what we face.

Most clean economy companies’ approach to elected officials doesn’t mesh with political reality

In nearly 20 years of serving clean economy companies, I’ve met tons of smart, inspiring people. But I’ve met fewer than 10 who’ve ever worked professionally in politics – actually getting paid to put politicians into office, working to keep them there, or kicking them out. By contrast, mature industries make investments in recruiting political talent as part of their government affairs (also known as “public affairs”).

Our pronounced lack of experience is a sign of our immaturity in public case-making. It’s also produced a collective mindset grounded in wants, not reality. We want politics to be a meritocracy, so we don’t treat it as the full-contact pressure game it’s always been.

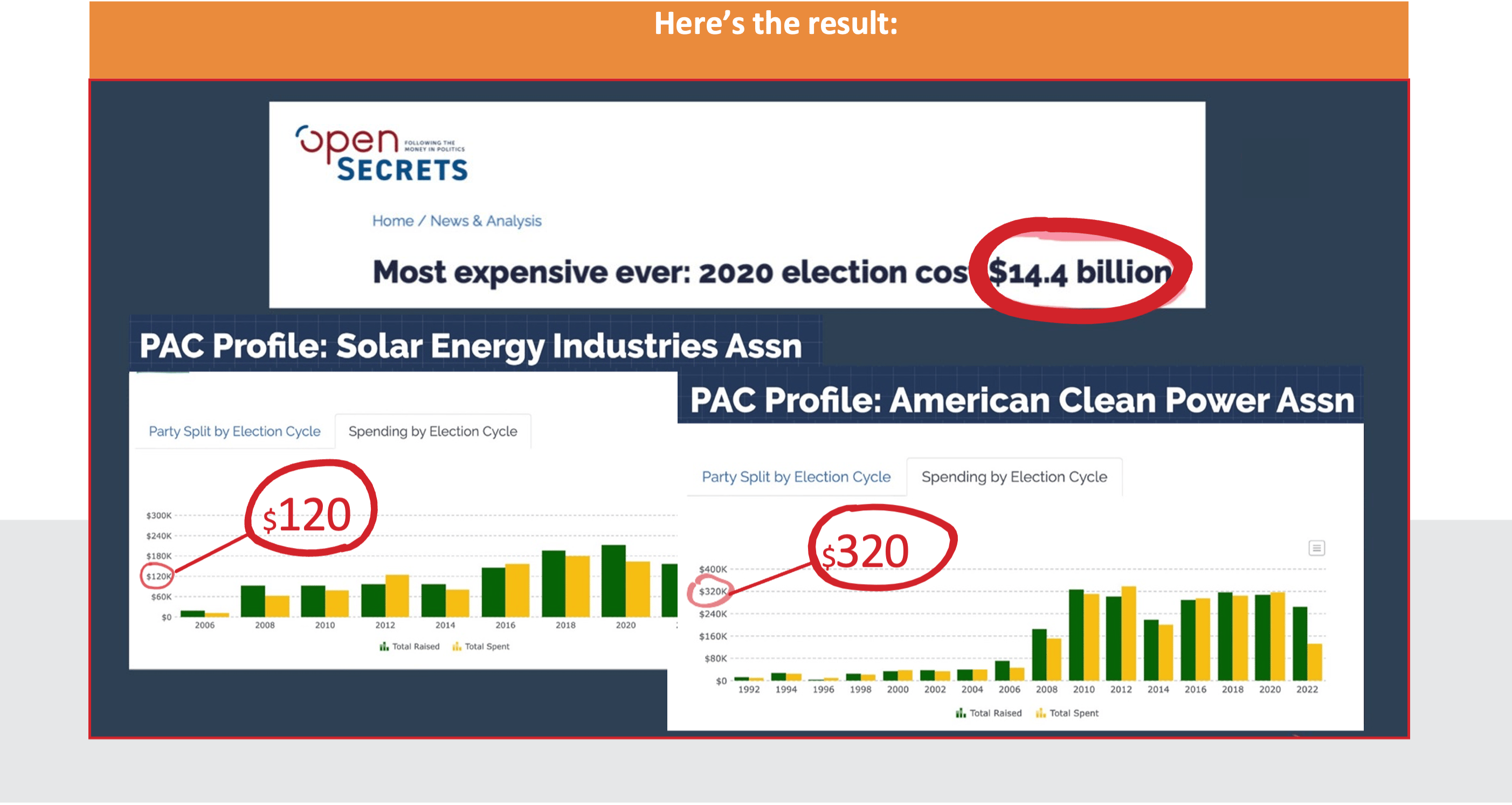

In election cycles now costing $14 billion, the ACPA and SEIA political action committees raise and spend $320,000 and $200,000, respectively. For context, the ACPA spending total is a bit over 2 one-thousandths of a percent of current election cycle spending.

If the history of lobbying and government tells us anything, it’s that politicians rarely lead, but they almost always respond to perceived political danger. And we provide none of that. That means we’re political beggars. Is it any wonder that Joe Manchin and dozens of senators and governors treat us accordingly?

Here's the result:

Manchin is our norm, not an exception

Yeah, Joe Manchin’s a tool. Not a “tool” in the popular culture sense – although if that’s your view of him, I won’t argue. I mean that he’s a tool of a fossil fuel lobby that’s been building political power for market gains over decades.

Scorpions sting because they’re scorpions. Dogs bark because they’re dogs. Manchin and most politicians weathervane on issues because that’s what politics rewards. In working with several hundred office holders and seekers earlier in my career, I found most had only the loosest mooring to an expressed ideology. The rest of their behavior is driven by fear of perceived electoral danger, combined with a nose for political opportunity.

Sen. Manchin seems to enjoy being the object of so much attention, so let’s unpack his observable behavior a bit. Big on his roots in poverty-stricken West Virginia but opposed minimum wage hikes and mandated family leave. Loudly asserts “Washington sucks,” but defends the Senate filibuster, among the most “Washington” of the capital’s most dysfunctional, arcane features. Or take this spread eagle, which I saw up close in 2018. That June, Manchin helped break ground on ROCKWOOL’s new factory to make its eco-friendly insulation in Jefferson County.

But after this groundbreaking, a group of County residents began aggressively objecting to the plant. By September 2018, Manchin had developed strong enough “concerns” to demand the U.S. EPA investigate the projected environmental impacts of the plant (no problems were found). Keep in mind that Jefferson County competed to host this plant, and Manchin has a staff of roughly 70 people. Does anyone really believe the Senator learned how the factory would operate only after he helped break ground for it?

Manchin is just another B.S. politician. Yet in an evenly divided Senate, he’s a uniquely empowered, B.S. politician. And not one who started as our buddy. After all, he had himself filmed shooting climate progress legislation with his deer rifle.

So, Joe Manchin is open for business.... Political business. We should see him as an invitation for advancing how we make our case to public officials. Because when it comes to how we secure fair treatment from policymakers, we need to grow up – and fast.

Politicians don’t lead, they respond to pressure

(H/T to Chris Lehane).

Upping our collective game starts with understanding how politicians relate to an economic or lobbying interest. It’s a three-stage process.

First, politicians must fear that a sector or interest group can impose electoral consequences if they cross it. Second, that fear – if properly induced – can lead them to respect that economic sector and account for its interests in their votes and positions. Electoral fear converts to fairer consideration. Third, if the politician perceives a strong enough risk-to-reward ratio, they’ll begin to champion that interest for political benefit. Nothing personal. It’s just what American voters have trained into their politicians over time.

I watched former U.S. Senator Dean Heller (R-NV) go through this evolution during his time in Congress. He started as a Tea Party Congressman who mocked clean energy in the wake of the phony Solyndra non- scandal: “My position on energy is that I want cold beer when I open the refrigerator and hot water for my shower.”

The then-Wind Energy Foundation (a former client) mounted the “A Renewable America” (ARA) campaign. That effort used an early version of relational organizing, in which campaigners harness peoples’ personal networks to virally spread messages.

The campaign produced content showing that many small clean energy businesses employed the rural Nevadans who formed Heller’s political base.

Heller’s out of office, and enough time’s passed that I can provide a look under the hood. ARA content was targeted at Heller’s top in-state staff and his closest friends – along with their respective social networks. At the same time, several solar companies chose to be public about expanding their presence in the state after then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid opposed NV Energy’s plans to build three coal plants around Ely, Nevada.

That change in the issue landscape just happened to coincide with Heller’s evolution into a self-styled clean energy supporter trying to out-champion his rivals on renewables. Heller’s change was triggered really through communications, not the sort of formal investment in community engagement that I argue for in this paper. But the point is that Heller’s change was partly spurred by seeing that mocking clean energy insulted real base voters.

Yet ARA’s approach is still an isolated exception, mostly funded by green philanthropy. Since then, I’ve only seen two companies use these principles on a limited, temporary basis. Most cleantech companies still shy from the political law of physics (fear → respect → champion) for reasons that are unclear to me. Too much coastal-state orientation? Are disruptor budgets defaulting to small thinking? Or the scarcity of professional political experience within our ranks?

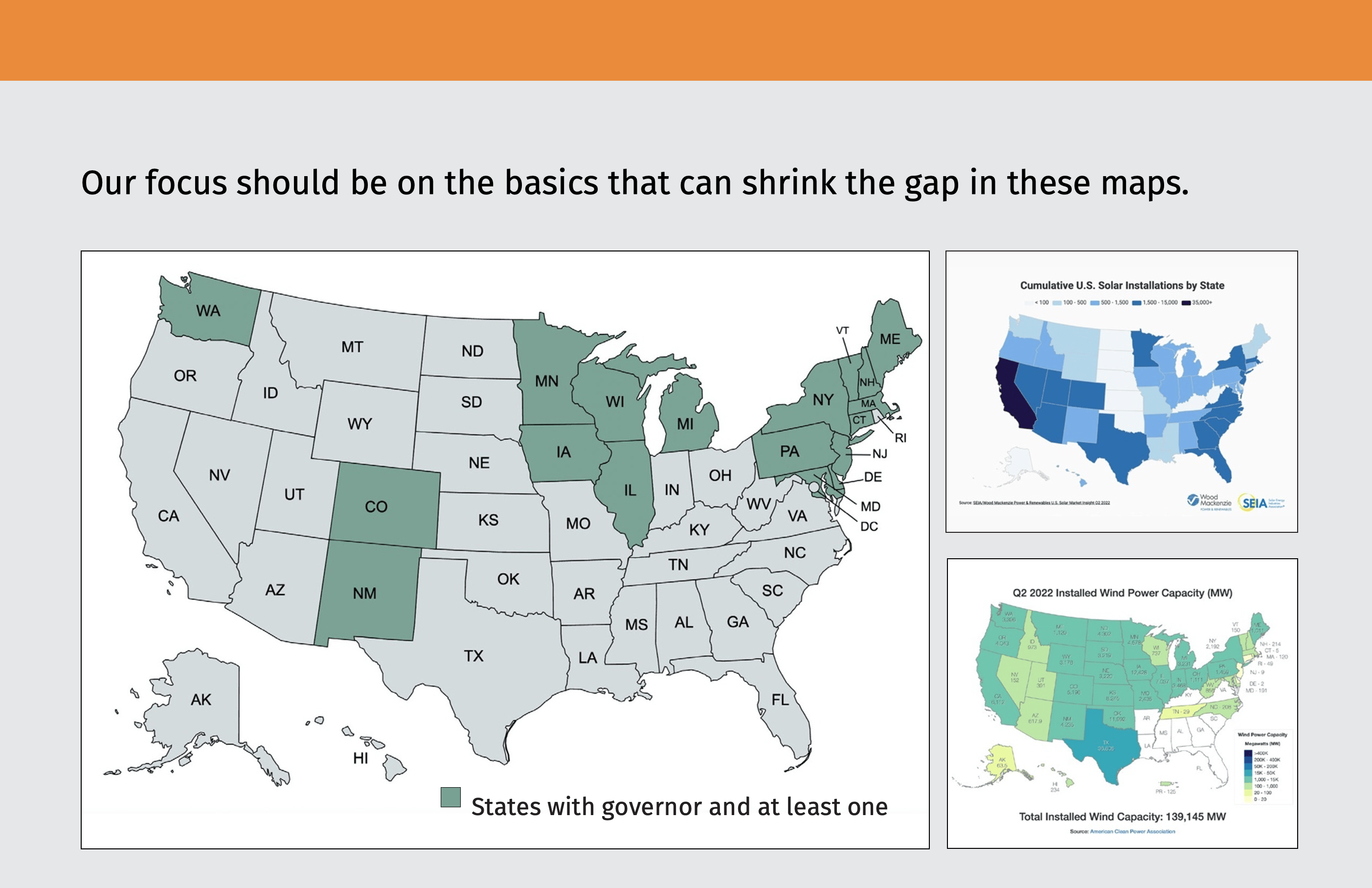

We must close the gap in the maps

There is an obvious difference between the maps of the states in which solar and wind are an economic presence and the states with public officials who champion renewables.

Can you imagine mature industries such as car dealers, home builders, or natural gas frackers tolerating such a gap in their maps?

Note: As we formatted this paper, Bloomberg News’ Liam Denning and Jeffrey Davies posted a story with a different map on this issue. It’s worth reviewing.

Treating West Virginia as a proving ground

Policy is made by weathervane politicians who respond to pressure. We can complain about or work with that reality. It’s our choice. But remember the energy sector we’re taking market share from has decades of practices and programs to exert political pressure.

If you live in West Virginia, you can:

- Attend the West Virginia Oil & Gas Festival every September in Sistersville, complete with an Oil & Gas Expo, Old Gas Engine Show, WV Oil & Gas Person of the Year Luncheon, Festival Queen, and Grand Oil & Gas Trophy Parade.

- Visit the Early Oil and Gas Industry Museum in Parkersburg.

- Apply for a scholarship to the Tom Dunn Energy Leadership Academy at West Virginia Wesleyan College. The program was established to “educate” young West Virginians who want to work in the fracking industry.

- Even get a license plate showing you’re an oil and gas industry supporter.

All these steps make oil and gas – fracking, really – a part of the cultural fabric of the state. You can bet your mortgage the fracking industry ensures Sen. Manchin perceives that his voters see fracking as a mainstay and essential. I also suspect that national and international oil and gas interests are running resources to lobby Manchin through the Gas & Oil Association of West Virginia, lobbyists close to Manchin—or both.

Sure, such programs require resources that many clean economy companies can’t match. But no clean economy company can poor-mouth why they skip the basics that can close the gap in the maps. As I write this, there are three major wind farms (totaling 376 wind turbines) operating in Manchin’s state. Each costs hundreds of millions of dollars to build, according to Metro News. But it’s unclear that even $1 was spent on ongoing programs to help renewable energy company neighbors know how they benefit.

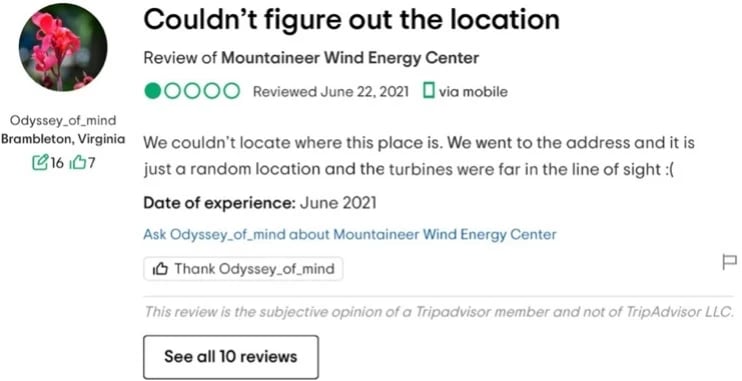

Take the Mountaineer Wind Energy Center wind farm. When it came online in December 2002, it was the largest east of the Mississippi River. It’s an important project, but no one shows it off to locals, much fewer visitors. Good luck even finding it now:

And of the 120 solar installers in West Virginia, we found little evidence that any show local voters they employ people, contribute tax revenue and drive economic activity. H/T to one exception: Solar Holler (see here and here).

To be clear, the blame doesn’t sit on the shoulders of any of these companies, their founders, or investors. This is a sector-wide problem created by years of treating public case-making as an afterthought. The global climate destruction crisis now requires an industry-wide solution. And as Ken Silverstein discusses in this compelling piece, West Virginia is as good a place as any to advance the way we make our case to elected officials.

Renewables have an early, growing presence. Now is the time for an industry-wide investment to help in-state clean energy companies pioneer a new approach to:

- Continuously making their case to neighbors that they’re an asset to the local economy through a strategic clean energy communications plan.

- Earning and growing community support through scaled community relations programs. We recommend our “1% Approach” here.

- Demonstrating community support in ways that instill political caution into officials.

Most clean economy sectors are new sectors within industries dominated by incumbents who aren’t interested in handing market share and profits over to the upstarts. Appreciating that reality is the starting point for the hard work of advancing a clean economy’s fortunes.

I’ll close with a challenge: Can you identify any elected official, in any state, at any level of government, who fears politically crossing the U.S. renewables industry? Until there’s a lot of them, we’ll continue relying on begging and luck.

“In this insightful article, Mike Casey breaks down how we as cleantech industry are succeeding in important areas but failing to exercise our strengths in the political arena due to lack of understanding. Mike provides suggestions for closing this gap.”

- Dan Shugar, CEO of Nextracker.

“What a fantastic and brilliant article from Mike Casey and his team! His insights into this important topic are invaluable.”

– Kimberlee Centera, CEO of TerraPro Solutions.

”Thoughtful piece at a critical time.”

– Stephen Smith, Executive Director of Southern Alliance for Clean Energy.

“Brilliant analysis.”

– Andrea Luecke, Executive Director of Cleantech Leaders Roundtable.

“Super article that is well worth a read by anyone who is interested in the politics of climate, whether US-based or not.”

– Christopher Caldwell, CEO of United Renewables and Host of Conversations on Climate.

“Worth the read!”

- Mark DelFranco of The Renewables Consulting Group.

“Political beggars” — brutal to hear, but it’s right.”

- Julia Pyper, VP of Public Affairs at GoodLeap, host of Political Climate podcast.

Author: Mike Casey

For 30 years, Mike Casey has focused on the design, staffing

Research assistance from: Jamie Meckley, Phoebe Lease, Nathaniel Schub & Alex Petersen.